It is often said the climate challenge is as much a political and moral challenge as it is a technical one. In technical terms, science gives us the evidence we need to address climate-related problems, and we have technologies and good practices that should be able to eliminate global heating caused by human activity. Whether we do the right thing is a moral question; it is also a question of what we value, and how precise we are in understanding where value comes from.

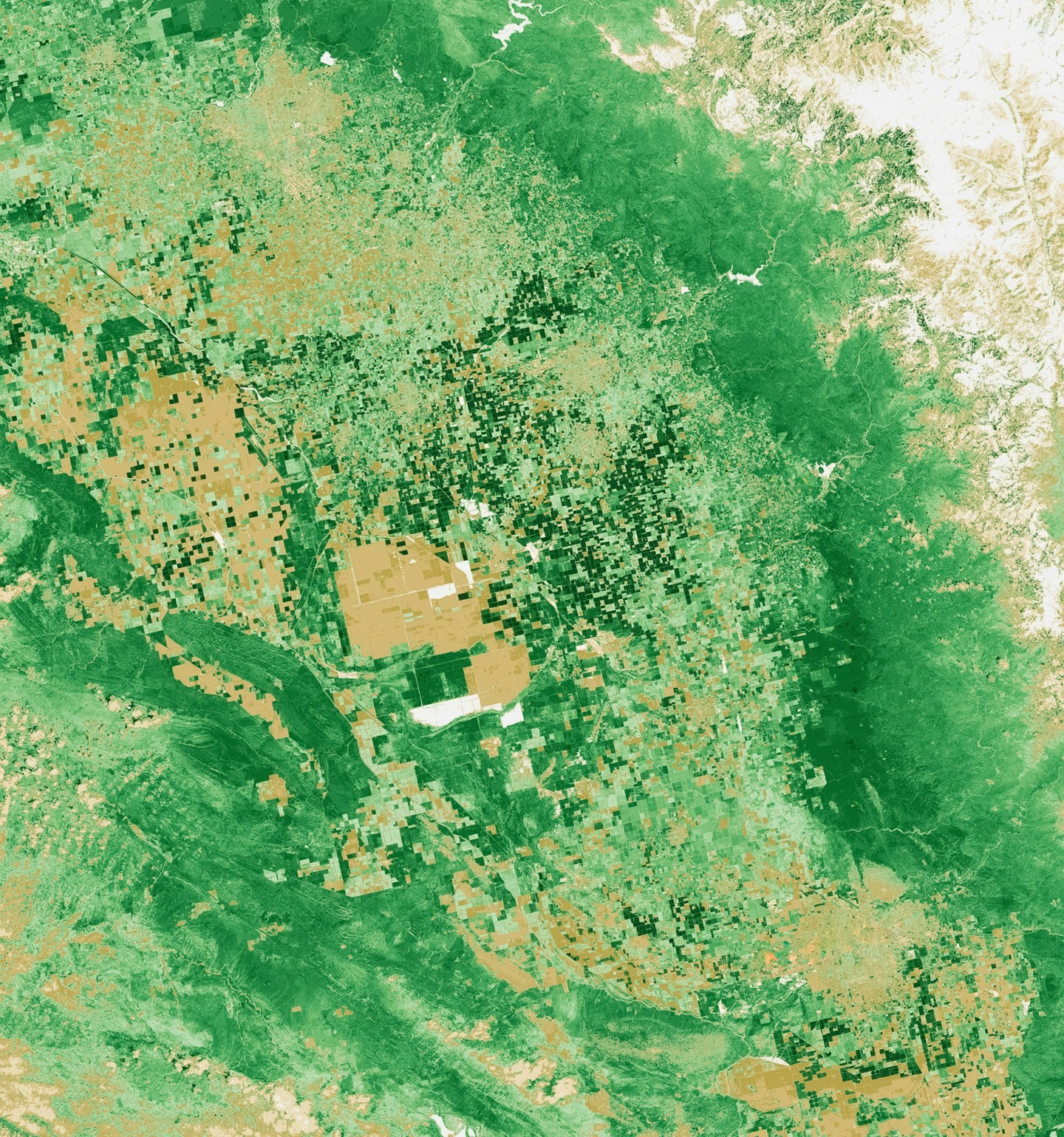

Though agriculture depends on Nature; we have tended to treat the two as adversaries. Natural environments are cleared and replaced with artificial environments, to maximize human control over the landscape and, in theory, maximize productive output. The reality, however, is that such practices destroy irreplaceable value and undermine the overall efficiency of agriculture.

This value destruction has ripple effects. Because the financing of agriculture depends on this premise—that land, Nature, water, and other ingredients of productive agriculture are resources, to be harnessed, whose value must be extracted and transferred to investors and consumers—the idea of value is built around how much financial gain can be achieved immediately, not over time.

This has the effect of incentivizing destructive practices, and it creates glaring conflicts of interest. The same banks that finance destructive land use practices also finance companies that provide artificial solutions to the harm caused to natural systems. The same companies may also be supporting clear-cutting, providing equipment that further depletes the ecological richness, water retention, and natural fertility of soils, then selling the fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds that are designed to fill in for the natural foundational value that has been destroyed.

Those companies are not charged a fee for the destruction of underlying value. They are not fined for inducing farmers to undermine the natural productivity of their land. They are not marginalized by markets for undermining watersheds and ecosystems or depleting pollinator populations. Instead, they are rewarded for squeezing Nature, which adds cost to the overall process of producing food.

Some of that added cost is embedded in food prices, because producers must pay for the remedies to destructive land use practices. But much of the cost is not embedded; instead, it is hidden, until it resurfaces in disaster response measures, related to drought, floods, fires, and other effects of industrialized global heating and climate disruption.

When farmers cannot afford insurance, the difference must be made up by taxpayers or by consumers. Or, the farming economy of the affected region begins to collapse, as fewer small farmers can make a living, and rural economies go quiet, with little new opportunity, no access to bridge financing, and margins too thin to sustain operations, especially in the face of rising costs due to climate disrution and Nature loss.

Regenerative land use strategies aim to not only transition farmland away from destructive practices. They aim to make the health of Nature an implicit area of value. This can filter out to the wider economy. Whether through effective competitive advantage, consumer interest, public policy and incentives, or financial prioritization of value-building practices, regenerative land use can reward those who build non-financial value and incentivize development of an economy that is good for Nature and builds climate-related value, while reducing costly risk and harm.

Even better: Farmers who effectively implement regenerative land use strategies can enrich the subsurface ecology, which means: healthier soils, enhanced natural fertility and productive capacity, more resilient soils, less prone to runoff from wind and water. All of that means land that is more stable and more insurable, which means it should be easier to access credit and work through hard times when they come.

Regenerative land use practices can also allow existing commodities markets to integrate resilience and climate-related value, boost farm goods that bring a green premium, and attract new investment to those practices, without having to turn Nature itself into a commodity. We will explore this further in future writing, but the essence is this: Nature-positive commodities should be actual farm goods and financial instruments that support sustainable practices, not commodified land, water, ecosystems, or species.

A key insight we wish to contribute to the discussion around climate-related food systems innovation and transformation is that how we use land filters through to and shapes the whole economy. This happens through prices, and the underlying math behind what margins are available for whose profit, and what that means about the appetite for investing in better practices. It also happens through hidden costs that are eventually carried by all of society, and which are almost beyond imagining.

Undervaluing the foundational value of healthy watersheds and ecosystems—including soils, biodiversity, and non-commodity vegetation—has threaded hidden costs throughout our economy, undermining net household incomes and local economic progress in all regions. As regenerative practices spread, they will become a key point of leverage for sustainable finance leaders, who will effectively build the economy of the future and secure their market position.